The Rise of “Let’s Dabke”

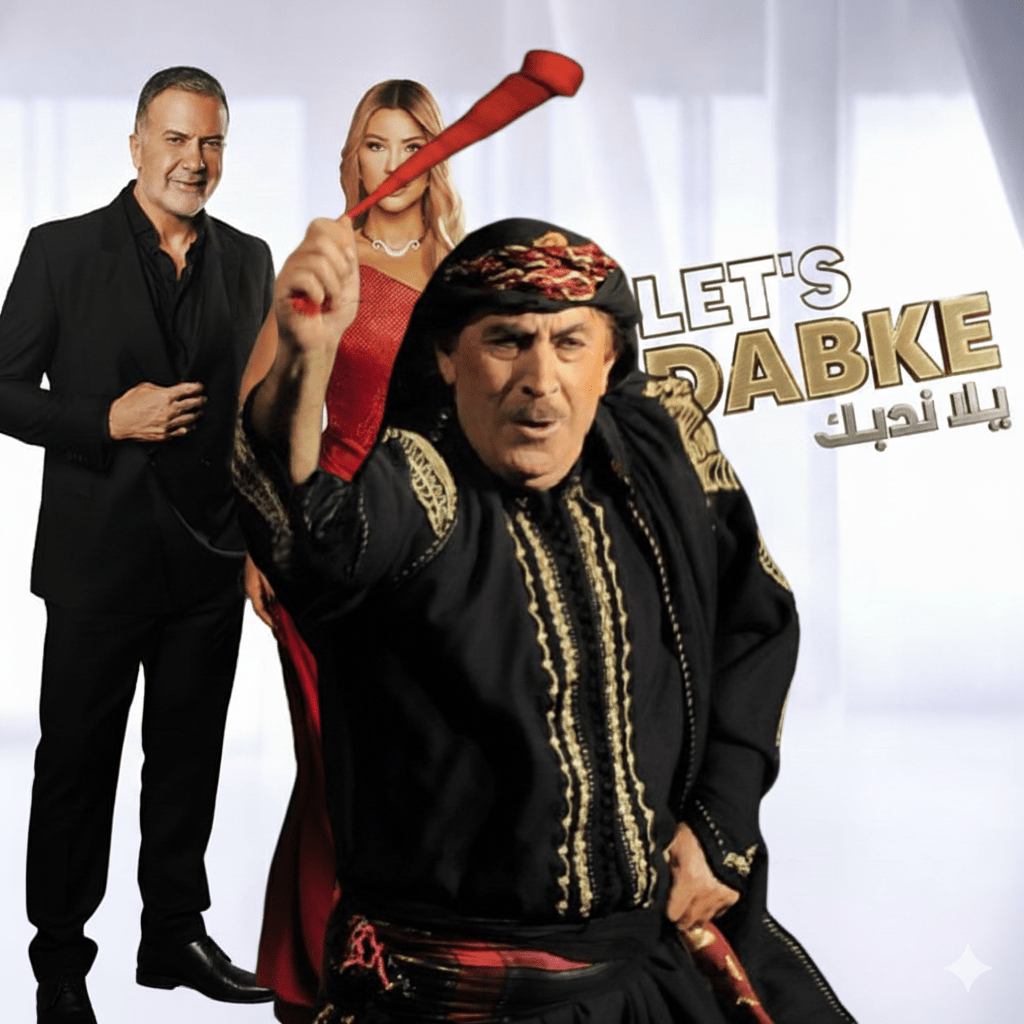

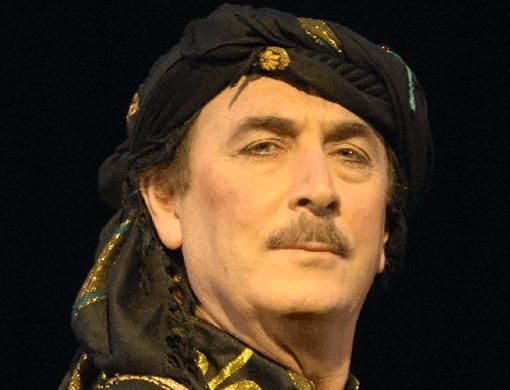

MTV Lebanon’s hit show Let’s Dabke (يلا نندبك) is more than a dance competition. It’s a stage for Lebanon’s most talented dabke troupes to showcase rhythm, creativity, and cultural pride. With a judging panel that blends tradition and modernity—Omar Caracalla (Baalbek’s ritualist and theatrical innovator), Dr. Nadra Assaf (dance scholar and feminist voice), and Rabih Nahas (former Dancing with the Stars judge and champion)—the show promises entertainment with depth.

Yet from episode one, it became clear this program was about more than footwork. When the Al-Afandiyya troupe from the Bekaa, led by Manwa Al-Afandi, featured a woman leading the dabke line, it ignited a cultural debate.

The Controversy: Women Leading the Line?

Omar Caracalla responded sharply: “In Baalbek’s tradition, women do not lead the line.”

Dr. Nadra Assaf pushed back, questioning the rigidity of such rules in a modern, evolving Lebanon. Rabih Nahas supported the performance, praising its artistry and spirit.

Suddenly, Let’s Dabke wasn’t just a competition—it was a mirror reflecting Lebanon’s deeper cultural disagreement: What is Dabke? And more importantly, who gets to define it?

The Larger Debate: What Is Dabke Really?

Just like Lebanese politics, there is no national consensus on dabke. Instead, there are multiple rhetorics, shaped by geography, history, and ideology.

Baalbek’s Narrative: Ritual, Rhythm, and Masculinity

In Baalbek, dabke is ritual before it’s performance. It descends from Bedouin ‘arda (sword dances), shaped by centuries of tribal expression. Masters like Abu Yehya, Abu Majed, and Abu Doukhi preserved six core styles:

- عرجة (Arja)

- بداوية (Bedouin)

- شمالية (Shmaliyya)

- زينو (Zaino)

- عسكرية (Askariyya)

- طيراوية (Tirawiyya)

Here, men lead. The line is sacred. The step is not only movement—it’s declaration. Dabke is a choreographed code of identity, strength, and discipline.

Alternative Views: From Phoenicia to the Diaspora

Some Lebanese scholars and communities claim Phoenician or Aramaic origins. Zaki Nassif famously suggested dabke emerged from villagers stomping mud roofs flat after rainfall—a functional act turned art. Others note that “Dalaouna” is Aramaic for “help one another,” suggesting communal roots.

These views emphasize symbolism, not ritual. They see dabke as inclusive, expressive, evolving. In this world, women leading isn’t controversial—it’s celebrated.

Regional Variants and Global Spread

Dabke lives across borders—Palestine, Jordan, Syria, and parts of Saudi Arabia have their own forms. Diaspora troupes in Europe and North America fuse styles, reflecting aesthetics over ancestral rule. Lebanese schools like Zorba Academy or Dabke Baalbackieh strive to balance tradition with accessibility.

Conclusion: Dabke as Lebanon’s Cultural Mirror

The debate on Let’s Dabke wasn’t just about who leads the line. It was about legacy, identity, and cultural evolution. Omar Caracalla reminded us of dabke’s sacred ritual codes. Dr. Nadra Assaf championed its potential as inclusive expression. Rabih Nahas celebrated its performative versatility.

In the end, dabke reflects Lebanon itself: rich in history, rooted in pride, and always negotiating the space between past and future.

Whether you clap, stomp, or simply watch—you’re part of the story now.

Leave a comment