How did the Dabke—once danced on rooftops and village squares—reach international festivals and satellite TV? The answer lies in a century-long transformation of Lebanese music and cultural identity, driven by war, migration, and visionary artistry. This is the story of how Lebanon’s most iconic musical and dance traditions adapted to modernity without losing their soul.

Early Roots and Urban Transformation (1900s–1940s)

At the dawn of the 20th century, Lebanese music was rural and organic. It lived in weddings, harvests, and village gatherings, driven by the beat of the tabl and derbakki, and enriched by folk instruments like the rababa and mijwiz. The Dabke line was more than a dance—it was a communal ritual accompanied by chants, circular breathing, and rhythmic stomping.

The turning point came in 1938 with the launch of Radio Lebanon. A teenage Wadih El Safi won a national singing competition and began reinterpreting the melodies of Mount Lebanon. His success signaled the start of a new era—one in which rural sounds were introduced to urban audiences, adapted for microphones, and preserved through vinyl and radio waves.

The Theatrical Golden Age (1950s–1960s)

By the 1950s, the push to create a distinctly Lebanese national sound intensified. The Rahbani Brothers, alongside Fairuz, led a movement that transformed folk songs into musical theatre. Their productions—like “Jisr el Qamar” and “Ayyam el Hassad”—combined poetic lyrics, Dabke beats, and fictional village narratives that resonated across class and region.

The crowning moment came in 1957, when the Baalbeck International Festival launched its “Lebanese Nights” series, placing folklore on the same stage as Beethoven and Shakespeare. The Dabke was no longer just a village dance—it became the centerpiece of choreographed stage performances.

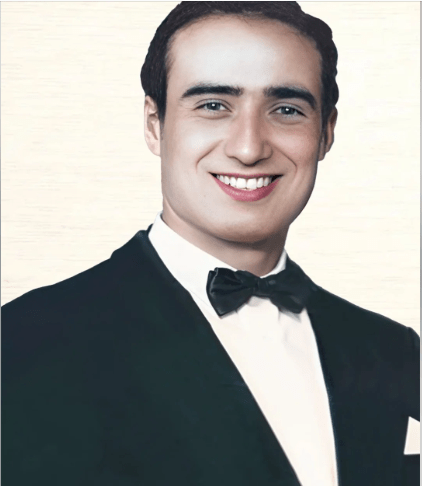

Nasri Shamseddine played the archetype of the wise village man, while orchestras blended ouds, qanuns, violins, and accordions with Western harmonies. This was Lebanon’s folklore reborn—not as nostalgia, but as national art.

War and Innovation (1970s–1980s)

The Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) halted much of the public cultural life, but it could not silence it. In fact, the war catalyzed a wave of innovation. Artists took their message abroad, performing for exiled communities and reshaping the national sound.

Ziad Rahbani, son of Fairuz, revolutionized Lebanese music by merging jazz, funk, and classical Arabic melodies. His instrumental track “Abu Ali” became an underground hit across Europe and the Arab world. Meanwhile, Fairuz’s patriotic songs united a fractured nation from afar.

The 1980s saw the rise of electronic keyboards, synthesizers, and drum machines. These tools gave traditional rhythms new life, birthing genres like Arab disco. Pop singers like Majida El Roumi and Ragheb Alama blended romantic ballads with danceable beats, appealing to new generations.

Post-War Revival and Pop Fusion (1990s)

Following the end of the war, Lebanon experienced a cultural rebirth. The Baalbeck Festival returned in 1997. Before that, in 1994, Fairuz’s concert at Martyr’s Square—attended by over 40,000 people—marked a national catharsis.

The 1990s gave rise to a new generation of stars. Najwa Karam embraced pure Dabke-pop, fusing electronic brass with traditional percussion to revive folkloric themes in nightclubs and wedding halls. Her energetic beats preserved the Dabke’s cultural roots while making it accessible to a globalized youth.

Meanwhile, Beirut’s alternative scene witnessed bands like Soap Kills, who pioneered Lebanese trip-hop by blending Arabic poetry with digital production. They symbolized a new form of cultural expression—urban, eclectic, and unafraid to blend East and West.

Legacy: Balancing Tradition and Change

Over the 20th century, Lebanese folk music evolved without erasing its identity. While the instruments changed and stages got bigger, the core—the beat of the Dabke, the call of the mawwal, the pride of village rhythm—remained. The music of Lebanon did not just survive—it reimagined itself with every war, every migration, and every new technology.

Today, the Dabke beat lives in Fairuz’s old vinyls, in wedding playlists, in underground clubs, and in international festivals. It’s the heartbeat of a nation that refuses to forget where it came from.

Leave a comment