Once danced on muddy rooftops and sun-drenched village squares, Dabke has transformed into a sophisticated stage performance shared on the world’s grandest stages. But this transformation didn’t happen overnight—it began with a cultural decision in 1957 that changed Lebanese arts forever.

The Cultural Turning Point

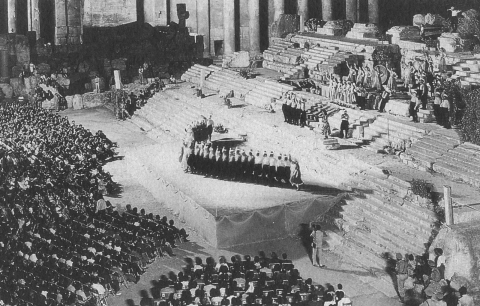

The Baalbek International Festival, founded in 1956, initially focused on Western classical music and European performances. But in 1957, First Lady Zalfa Chamoun insisted on integrating Lebanese rural traditions into the program. That decision introduced folklore—and Dabke—to Lebanon’s most prestigious cultural platform.

The same year, the first folkloric musical, Ayyam al-Hasad (Harvest Days), took place under the direction of Sabri al-Sharif, with a cast including Fairouz and the Rahbani Brothers. It was the birth of a national genre.

The Role of the League of Five

Behind the scenes, a group of composers and thinkers were shaping a uniquely Lebanese identity in music and dance. Known as the “League of Five”—Zaki Nassif, the Rahbani Brothers (Assi and Mansour), Tawfiq al-Basha, Philemon Wehbe, and Afif Radwan—they sought to elevate local traditions above the dominance of Egyptian and Bedouin styles.

They introduced extended melodies, orchestral structure, and folk-rooted lyrics to create a new Lebanese sound. This shift made Dabke suitable for theatrical storytelling and set the stage for refinement.

From Village Step to Stage Performance

To professionalize Dabke, dancers Marwan and Wadiaa Jarrar were sent to Russia to train under Igor Moiseyev. They returned with new techniques, fusing them with village steps to form the Lebanese Popular Troupe.

Costumes evolved from traditional shalwars and keffiyehs to stage-specific designs. Lighting, story arcs, and music composition played key roles in turning Dabke into theatre. Fairouz, with her haunting voice, became known as the “Seventh Column of Baalbek Temple,” symbolizing the sacred union between heritage and performance.

Caracalla’s Bold Leap

In 1968, Baalbek natives Abdel Halim and Omar Caracalla founded the Caracalla Dance Theatre. Inspired by Bedouin life and trained in Paris and London, the Caracallas blended Dabke with global dance traditions. Their debut show, The Black Tents, imagined a nomadic tale told through Lebanese rhythm and Western choreography.

Over the next five decades, Caracalla performed in more than 70 countries, reintroducing Lebanon through dance in Paris, New York, and Beijing.

Women at the Front

Traditional Dabke often excluded women or placed them behind curtains. Theatrical Dabke flipped the script. Fairouz danced on the front lines. Wadiaa Jarrar helped choreograph. Elissar Caracalla later led Caracalla’s modern direction. Today, female dancers are central to both performance and pedagogy.

Authenticity and the Future

Dabke’s popularity on social media has brought both joy and concern. Purists like Moussa Shalha worry that speed and showmanship are replacing form and storytelling. Debates continue: is theatrical Dabke too polished? Is it drifting from its rural soul?

Still, institutions like Caracalla School, Hayakal Baalbek, and university clubs keep the dance rooted in its core: rhythm, pride, and land.

From roof to spotlight, Dabke’s journey continues—not just as a dance, but as the heartbeat of Lebanese identity.

Leave a comment